Bovine tuberculosis in cattle is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium bovis, a bacterium belonging to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. TB in cattle primarily affects the lungs but can spread to other organs, causing progressive illnesses like Lymph nodes, the Alimentary tract, Udder, and some other organs, too, like the liver, spleen, kidneys, and even brain. Cattle with tuberculosis often show signs like a persistent cough, gradual weight loss, weakness, and a drop in milk production. The impact goes beyond cattle health; the disease can also spread to humans. That’s why it’s a serious issue not only for farmers but also for veterinarians and public health professionals, particularly infants, where disease control efforts are lacking.

Bovine tuberculosis has been known for more than a hundred years, with some of the earliest reported cases dating back to 19th-century Europe. The disease gained international attention as it spread among cattle herds and infected humans through unpasteurized milk. Over the decades, national eradication and test-and-slaughter programs helped reduce its prevalence in many developed countries. However, in parts of Africa, Asia, and South America, bovine tuberculosis in cows remains endemic, contributing to ongoing transmission and economic strain on livestock-based communities.

Understanding how bovine tuberculosis spreads and develops is critical for those managing affected herds. The following sections explain transmission routes, symptoms, diagnostic methods, and available control strategies. Experts focus on early detection, consistent testing protocols, strong biosecurity measures, and the importance of coordinated surveillance efforts to reduce the burden of this persistent livestock disease.

Symptoms of Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

Bovine tuberculosis (bovine TB) is a slow-progressing bacterial disease that poses diagnostic challenges due to its vague and delayed clinical presentation. In the early stages, symptoms in cattle may include lethargy, reduced appetite, fluctuating fever, and gradual weight loss. These signs are often mild and may go unnoticed without laboratory confirmation or routine testing.

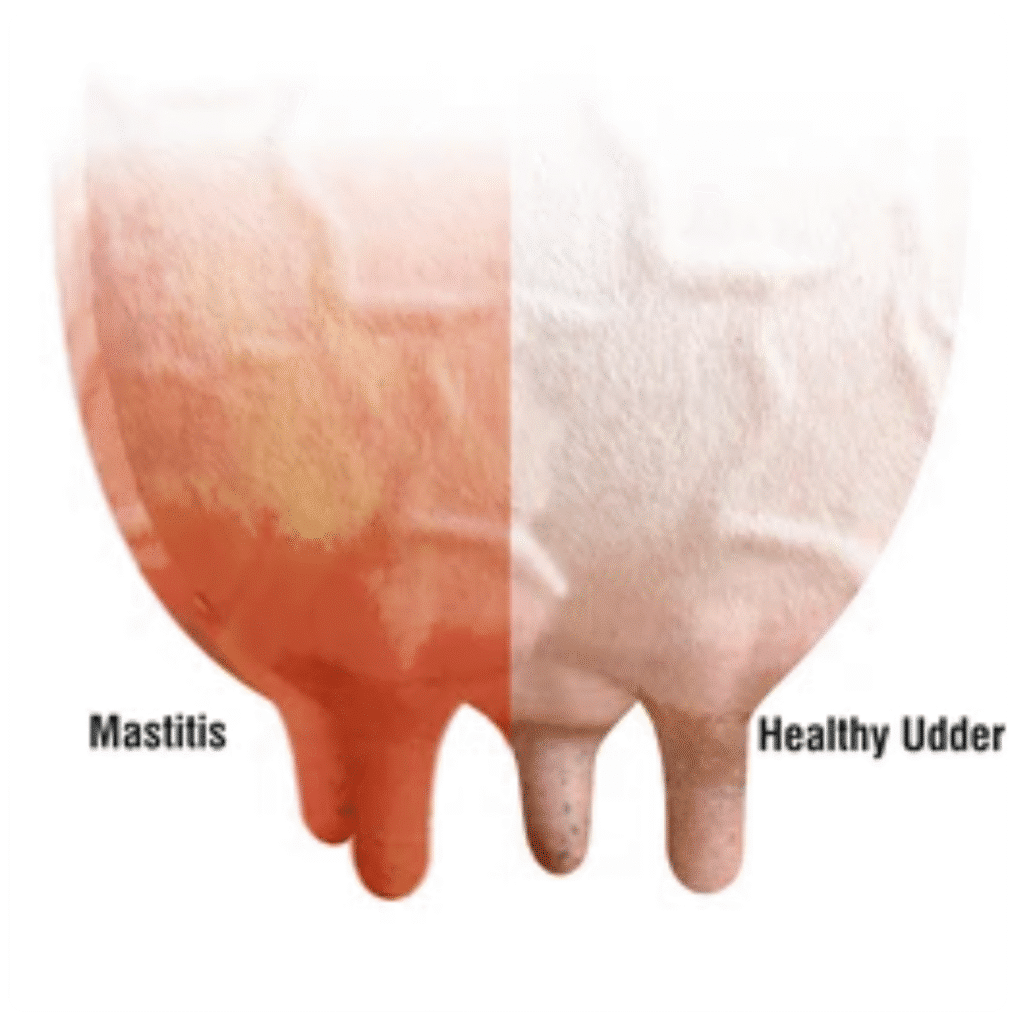

As the condition advances, more recognizable tuberculosis in cattle symptoms can appear such as swelling of superficial lymph nodes (especially in the neck), a moist chronic cough that worsens in cold weather or after exercise, and respiratory distress, including dyspnea and rapid breathing. In some cases, chronic mastitis unresponsive to antibiotics may signal underlying cattle tuberculosis.

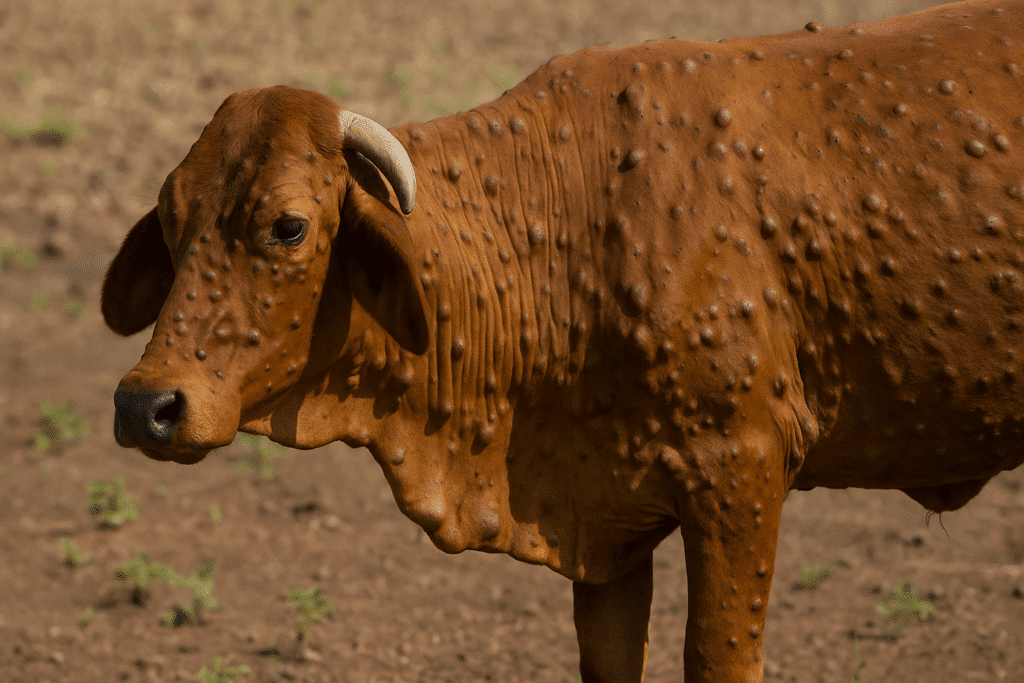

The range of bovine tuberculosis symptoms in animals depends on disease severity.  Internal lymph node involvement may obstruct the airways or digestive tract, leading to ruminal tympany or labored breathing. Occasionally, draining lymph node abscesses may mimic bovine skin conditions. Timely diagnosis and veterinary management are vital to controlling bovine tuberculosis in cows and reducing its impact on herd health.

Internal lymph node involvement may obstruct the airways or digestive tract, leading to ruminal tympany or labored breathing. Occasionally, draining lymph node abscesses may mimic bovine skin conditions. Timely diagnosis and veterinary management are vital to controlling bovine tuberculosis in cows and reducing its impact on herd health.

Causes of Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

Mycobacterium bovis causes bovine tuberculosis. A type of bacteria that belongs to the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC). This bacterium primarily affects cattle but can infect many mammals, including humans, making it a serious zoonotic concern. Once in an animal’s body, The bacteria can stay inactive for months or even years, then later cause long-term illness that affects the lungs, lymph nodes, and other organs inside the body. The disease spreads mainly through inhalation of infected droplets, But it can also spread by eating or drinking contaminated feed, water, or unpasteurized milk.

Unlike many cattle diseases, Mycobacterium bovis in cattle can silently circulate within a herd because symptoms often appear only in advanced stages. This silent progression makes early detection difficult. Stress, poor nutrition, overcrowding, and compromised immunity in animals can trigger the activation of the bacteria, increasing the risk of disease spread and severity. The infection can hide from the Animal’s immune system and stay inactive, which makes bovine tuberculosis hard to control and get rid of once it spreads in a herd.

Mycobacterium bovis: The Causative Agent

Mycobacterium bovis bacteria are slow-growing, rod-shaped organisms with a thick, waxy cell wall, making them highly resistant to environmental stresses and disinfectants. This unique cell structure contributes to their survival in the host and contaminated environments such as manure, soil, and water troughs. Their shape and structure often referred  to in microbiology as Mycobacterium tuberculosis shape are central to their classification and behavior in hosts. The tuberculosis morphology also helps explain the bacterium’s resistance to many conventional treatments and its ability to establish chronic infections.

to in microbiology as Mycobacterium tuberculosis shape are central to their classification and behavior in hosts. The tuberculosis morphology also helps explain the bacterium’s resistance to many conventional treatments and its ability to establish chronic infections.

These bacteria target the respiratory system first, entering through inhalation and settling in the lungs or nearby lymph nodes. The bacteria may spread to other body parts, including the liver, spleen, and digestive tract. The infection process is slow, giving bovine tuberculosis symptoms in cattle a delayed onset. Sometimes, the immune system can not completely remove the bacteria, so they remain dormant. The infection may become active if the animal becomes stressed or health declines.

Diagnosis of Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

Accurate bovine tuberculosis (BTB) detection limits its spread, especially in herds with no visible symptoms. Diagnosing this disease requires a well-rounded approach. Farmers and veterinarians rely on careful clinical observation, quick tests in the field, and more detailed lab work to detect Mycobacterium bovis. These steps help confirm infections early and shape the most effective control measures.

1.Clinical Assessment and Common Indicators

In most cattle, clinical signs are minimal or absent in early or latent infection, making diagnosis by observation alone difficult. However, veterinarians may note progressive weight loss, chronic moist cough, weakness, and a low-grade fluctuating fever. Some animals show swollen lymph nodes, particularly around the neck or head, and advanced disease may result in respiratory distress, such as labored or rapid breathing. Unresponsive mastitis and digestive issues like bloating can also suggest deeper internal involvement.

These signs are not unique to tuberculosis and may be confused with other chronic respiratory or systemic infections. Therefore, while clinical signs may guide initial suspicion, they must be supported by confirmatory diagnostic testing to ensure accuracy and prevent misdiagnosis.

2.Field Testing for Bovine TB (Tuberculin Skin Testing (SIT & SCIT)

The most established bovine tuberculosis test at the herd level is the tuberculin skin test. In the Single Intradermal Tuberculin Test (SIT), a small amount of bovine PPD (a purified protein derivative) is injected into the skin commonly at the mid-neck or tail-fold. Veterinarians check the site for swelling after 72 hours. They widely use this response in bovine TB testing programs, as it indicates prior exposure to M. bovis.

Veterinarians prefer the Single Comparative Intradermal Tuberculin Test (SCIT) for improved accuracy. This is especially important in regions where cattle frequently encounter other mycobacteria, such as M. avium. This method uses bovine and avian PPDs at separate injection sites on the neck to differentiate M. bovis infections from cross-reactions.

Both tests depend on proper injection technique, correct measurement using calipers, and interpretation by trained personnel. False-negative results can occur in immunocompromised or recently infected animals, while false positives are sometimes due to cross-reactive mycobacteria.

3.Clinical Confirmation via Necropsy and Pathology

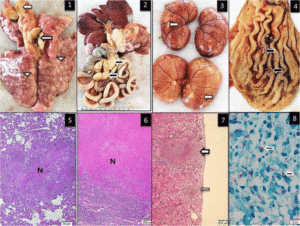

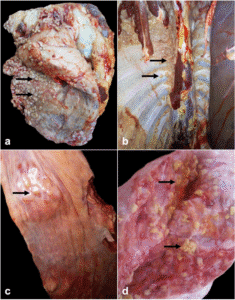

In suspected cases where animals are culled or die, post-mortem examination provides valuable diagnostic confirmation. Veterinary pathologists inspect lymph nodes and organs such as the lungs, liver, or spleen for granulomatous lesions, abscesses, or caseous necrosis hallmark features of bovine tuberculosis in cows. Tissue samples from these sites are critical for further laboratory testing, including culture and histopathology.

Finding granulomas with dead tissue in the center, surrounded by inflammation and fibrous tissue, is a strong sign of tuberculosis. When these results are considered alongside earlier skin test outcomes and the herd’s medical history, they can help confirm the diagnosis with confidence.

4.Laboratory Testing for Diagnostic Confirmation

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction):

PCR is a lab test that helps detect traces of M. bovis in tissue, blood, or mucus. It gives fast and accurate results, making it especially helpful during outbreaks or when early detection is needed.

Culture:

Although considered the gold standard, bacterial culture can take up to 15 weeks to grow M. bovis on specialized media. It remains critical for definitive diagnosis and strain typing, particularly in regulatory or international trade settings.

Interferon-Gamma Assay:

In vitro assay measures interferon-gamma release from white blood cells exposed to TB antigens. Veterinarians often use it as a supplementary test in cattle TB programs because it detects early infections more sensitively than skin testing. However, it requires rapid lab processing after blood collection.

Histopathology:

Pathologists can microscopically examine tissue necropsy samples to detect cellular changes specific to TB, such as caseating granulomas. This method complements culture and PCR tests, helping to confirm the presence and extent of infection.

Serological Testing:

To check for tuberculosis in cattle, vets often rely on cell-mediated immune responses, which naturally respond at the cellular level. Veterinarians occasionally use blood tests such as ELISA to monitor herd health, but it is not the most reliable way to confirm active infection since antibody levels can differ quite a bit between individual cows.

5.Practical Considerations for Field Application

Accurate diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis in cattle depends on coordinated efforts between veterinarians, diagnostic labs, and livestock owners. Routine surveillance through bovine TB testing, especially in high-risk or endemic areas, is essential for early detection and movement control. When symptoms appear, or cattle come into contact with TB carriers like wildlife, quick action using a combination of skin testing, necropsy, and lab confirmation ensures prompt containment and herd protection.

Treatment of Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

Bovine tuberculosis, or BTB, is a long-lasting bacterial infection caused by Mycobacterium bovis. While there is no approved direct cure for the infection, especially in countries that rely on test-and-cull strategies, the treatment of bovine tuberculosis in animals focuses on symptom control, supportive care, and disease containment. It becomes particularly important in remote regions or smallholder farms where access to veterinary services is limited.

Supportive management, immune system support, and the use of vaccines in certain cases can help stabilize infected animals, reduce transmission, and sustain productivity while maintaining herd-level biosecurity.

Supportive Management in Bovine Tuberculosis

Even though complete eradication in infected animal’s isn’t possible without culling, supportive management helps maintain animal strength and slows disease progression. Includes keeping animals in stress-free, well-ventilated areas, offering quality feed, and isolating infected cattle from healthy ones.

Nutritional and Immune Support

Strengthening the immune system improves an animal’s ability to fight secondary infections. Supportive supplements include:

- Multivitamins (A, D, E) to assist immune regulation

- Zinc and selenium to support healing and defense

- Probiotics and yeast-based supplements to improve digestion and immunity

- Oral electrolytes to maintain hydration and energy

These supplements can be especially useful for animals that seem weak and are not eating well.

Managing Secondary Infections

Secondary infections, such as respiratory tract infections or infected lymph nodes, often complicate bovine tuberculosis in cattle. Although antibiotics do not eliminate M. bovis, they help manage such complications.

| Condition | Recommended Action | Examples |

| Chronic moist cough or pneumonia | Antibiotic therapy + anti-inflammatories | Oxytetracycline, Enrofloxacin |

| Swollen lymph nodes or abscesses | Penicillin-streptomycin combo | Pen & Strep IM |

| Fever, pain, or joint inflammation | NSAIDs to reduce inflammation | Flunixin, Meloxicam |

| Weakness or dehydration | Electrolytes + immune supplements | Oral hydration + A-D-E vitamins |

| Recent calving or stress | Multivitamin-mineral support | Vitamin injectables |

Note: Treatment duration usually ranges from 5 to 7 days, depending on the response and severity.

Vaccination for Control and Prevention

Although not used for treatment, bovine TB vaccine strategies are being tested and used in some regions to reduce the disease burden, especially in endemic zones. The cow TB vaccine (BCG strain) helps reduce the severity and transmission of infection. Still, it is not currently approved for widespread commercial use in many countries due to interference with skin test diagnostics.

Farmers or veterinarians may consider vaccinating young stock against bovine tuberculosis in non-replacement animals or wildlife-livestock interface zones.

Field Hygiene and Biosecurity Practices

Without treatment options, biosecurity is your strongest line of defense. Key steps include:

- Isolate infected animals immediately to reduce herd exposure.

- Avoid shared feed/water troughs between healthy and sick cattle.

- Disinfect housing and equipment with phenolic or iodine-based solutions

- Control wildlife or other TB vectors like badgers, wild boar, or deer that may spread M. bovis.

Quick Reference Farmer’s Guide to Bovine TB Care

| Step | Action |

| Identify symptoms | Chronic cough, weight loss, swollen lymph nodes |

| Isolate affected cattle | Separate from the herd to prevent the spread |

| Provide immune support | Multivitamins, trace minerals, yeast-based feed additives |

| Manage secondary infections | Use antibiotics + NSAIDs as needed |

| Hydrate and feed well | Use oral electrolytes and energy-rich feed |

| Clean housing & equipment | Disinfect regularly and ensure good airflow |

| Monitor for worsening signs | Check breathing, appetite, and any visible swelling |

| Consult a veterinarian | As soon as available, especially for herd-level planning |

Transmission of Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

Bovine tuberculosis (BTB) is a chronic infectious disease that spreads silently and gradually within and between cattle herds. The infection is caused by Mycobacterium bovis, which can be transmitted through respiratory secretions, contaminated environments, and in some cases, wildlife reservoirs. Since the disease often progresses slowly and lacks early clinical signs, cattle may unknowingly spread the infection before they appear ill. The major factors influencing the transmission of tuberculosis bovina include inhalation of infected droplets, ingestion of contaminated materials, shared living spaces, and exposure to infected wildlife.

Respiratory Transmission: The Primary Route

The most common mode of bovine TB transmission in cattle is inhaling aerosolized droplets containing M. bovis. When an infected animal coughs or exhales in close quarters such as in barns or during transportation nearby animals may inhale these droplets and become infected. This form of transmission is particularly efficient in confined spaces with poor ventilation or high stocking densities. Bovine tuberculosis in cows often goes undetected for months, allowing them to infect multiple herd mates during the incubation period.

Oral Ingestion and Environmental Exposure

Although respiratory spread is dominant, cattle can also contract bovine tuberculosis by consuming feed or water contaminated with the bacteria. M. bovis may enter the environment through animals’ feces, urine, milk, or nasal discharge. Contaminated troughs, bedding, or handling equipment may be indirect transmission sources. Calves are especially at risk when they consume raw milk from infected cows, which can harbor viable bacteria.

Wildlife Reservoirs and Indirect Spread

Wild animals such as badgers, boars, and deer are known TB vectors in some regions, particularly Europe, North America, and Africa. These species may carry and shed M. bovis, introducing the infection into pastures or water sources shared with domestic cattle. This indirect route of transmission makes eradication more difficult and emphasizes just how important wildlife management is to any tuberculosis control program.

Animal Movement and Herd-Level Risks

Unscreened or undiagnosed animals moving between farms or grazing lands significantly spread bovine tuberculosis cattle infections. Animals in the early stages of infection may appear healthy but still harbor and shed bacteria. Using shared equipment such as milking machines, feed tools, or transport crates without proper disinfection increases the risk of spreading TB within and across herds. Poor biosecurity practices further accelerate this hidden transmission cycle.

Prevention of Bovine Tuberculosis in Cattle

Effective prevention of bovine tuberculosis in cattle requires a combination of herd health management, biosecurity, testing protocols, and control of animal movements. Since tuberculosis bovina spreads primarily through respiratory secretions and close contact, especially in confined or mixed environments, proactive strategies are critical for safeguarding herds particularly in endemic areas or high-density operations.

Surveillance and Early Detection

Routine screening through tuberculin skin testing or interferon-gamma assays is central to controlling cattle tuberculosis. Herds should be tested regularly according to national veterinary guidelines, especially before introducing new animals or moving livestock between farms. Detecting infected animals early reduces the chance of silent transmission and allows timely removal or isolation.

Biosecurity and Farm Hygiene

Maintaining strong biosecurity protocols is vital in preventing bovine tuberculosis in cows. It includes:

- Isolating new or returning animals for 30 days before integration.

- Cleaning and disinfecting equipment, water troughs, and transport vehicles regularly.

- Restricting access to farms by unauthorized personnel and wildlife that may act as TB reservoirs.

- Using designated tools and gear for different cattle groups to prevent cross-contamination.

By applying these practices, farmers significantly lower the risk of introducing or spreading tuberculosis bovina within their herds.

Wildlife Control and Environmental Management

In many regions, wildlife species such as badgers, deer, or wild boar are recognized carriers of bovine tuberculosis in cattle. Fencing off feeding and watering areas, reducing attractants, and managing interactions between livestock and wild animals can help prevent environmental transmission. Limiting access to shared grazing lands where TB-positive wildlife roam is also advised.

Herd Health and Immune Support

Unlike bovine respiratory disease prevention, improving cattle immunity plays a protective role. Well-nourished animals with minimal stress have a stronger ability to resist infections. Farmers should:

- Ensure balanced nutrition with adequate vitamins and trace minerals.

- Avoid overcrowding and improve ventilation in housing areas.

- Provide shade, clean water, and dry bedding to reduce stress and respiratory burden.

Controlled Movement and Regulatory Compliance

Preventing bovine tuberculosis in cows also involves strict control over cattle movement. Farmers should only purchase or bring animals from TB-free herds onto the farm. Always require health certificates and TB test results from suppliers. Follow national movement restrictions and reporting obligations for suspected or confirmed cases to avoid herd-wide or regional outbreaks.

Conclusion

Bovine tuberculosis continues to pose a major challenge in cattle herds because it spreads quietly, progresses slowly, and can infect humans. Detecting it early through regular testing and maintaining strong biosecurity practices is key to preventing widespread outbreaks. Although treatment options are limited, supportive care and measures to boost the immune system can help lessen Complications that can be hard to manage, which is why prevention is so important. Simple but effective measures — like limiting the movement of animals and keeping up regular health checks — are still the backbone of any successful control plan. On top of that, ongoing education, better awareness among farmers, and hands-on support from veterinarians are all crucial for protecting the health of animals and the wider community.

FAQs Related to Bovine Tuberculosis

What is bovine tuberculosis in cattle?

Bovine tuberculosis in cattle is a chronic infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium bovis. It primarily affects the lungs and lymph nodes, spreading slowly through respiratory droplets, contaminated feed, or contact with infected animals.

What are the five symptoms of tuberculosis?

Five common symptoms of tuberculosis in cattle include chronic cough, progressive weight loss, swollen lymph nodes, reduced appetite, and low-grade, fluctuating fever. These signs often appear in advanced stages of the disease.

What is the drug of choice for tuberculosis in cattle?

There is no approved drug for treating tuberculosis in cattle. Most countries prohibit the use of antibiotics due to concerns about public health, antibiotic resistance, and food safety. Instead, the disease is managed through test-and-cull programs, along with surveillance and strict biosecurity measures.

How do you diagnose bovine tuberculosis?

Bovine tuberculosis is primarily diagnosed using the tuberculin skin test (Single or Comparative Intradermal Test), which detects a delayed immune response to Mycobacterium bovis. For confirmation, laboratory tests such as PCR, culture, interferon-gamma assay, and histopathology are used to detect the bacteria or its genetic material in tissues or blood samples.

How to prevent TB in cows?

To prevent tuberculosis in cows, implement routine herd testing, isolate new or sick animals, and maintain strict farm biosecurity. Avoid contact with wildlife reservoirs, disinfect shared equipment regularly, and ensure cattle receive proper nutrition and stress reduction to support immune function. Only purchase animals from TB-free herds with verified health records.