Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis in cattle, also known as bovine rhinotracheitis, is a viral cattle disease caused by Bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1). The virus belongs to the Herpesviridae family, Alphaherpesvirinae subfamily, and Varicellovirus genus. Clinically, infectious bovine rhinotracheitis is characterized by respiratory abnormalities mainly involving the upper respiratory tract. IBR in cattle also affects the reproductive system, such as contagious pustular vulvovaginitis in females and balanoposthitis in males, and the virus can induce abortions in pregnant animals. These diverse presentations make the disease multifaceted and influential in both production and breeding contexts.

BoHV-1 poses a significant threat to cattle health and productivity. The virus rapidly affects animals through contact with infected droplets, equipment, or herd mates. Once inside the host, it multiplies in the mucous membranes of the respiratory or genital tract. After infection, the virus travels along the nerve pathways and settles in certain ganglia, where it stays dormant for life. During times of stress, it can reactivate, turning carriers into a hidden source of infection for the rest of the herd. Because of this silent risk and its negative impact on performance, early diagnosis and regular vaccination are essential for effective control.

The condition was first described in feedlot cattle in the United States in the 1950s following outbreaks of critical respiratory illness. Since then, it has become endemic in many regions due to its efficient spread and persistent nature. IBR is also endemic in the UK, with around 40% of cattle having been exposed to the virus in the past.

infectious bovine rhinotracheitis symptoms in cattle

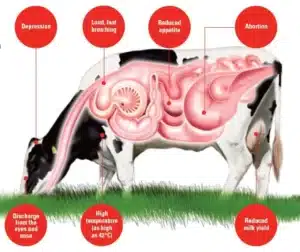

The first signs of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis often include fever (high body temperature, 41–42°C), depression, and loss of appetite, leading to noticeable weight loss. Early changes involve nasal and ocular discharge (runny nose and watery eyes) that starts clear and watery but may thicken into a pus-like fluid. As the disease progresses, red nose (rhinitis – inflammation of the nasal lining) may develop, often with nasal lesions (patches of damaged tissue) and trachea damage (injury to the windpipe lining), both of which can make breathing less efficient.

Affected animals may cough frequently, show dyspnoea (difficulty breathing), or develop halitosis (foul-smelling breath) from pus in the airways. Drooling of saliva can occur due to digestive slowdown, while conjunctivitis (red, swollen eyes) may appear with or without breathing issues. Many cattle also experience a milk drop (sharp fall in milk production) and an increased respiratory rate (faster breathing), even when abnormal lung sounds are absent.

The incubation period of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) is usually two to six days after exposure. During this time, cattle show no outward signs, but the virus is active in the body. Once symptoms appear, the disease can spread rapidly within a herd, with morbidity reaching nearly 100% in severe outbreaks. Mortality is typically low, under 2%, but rises if secondary bacterial pneumonia develops. Early detection is critical to reducing losses and limiting the spread.

Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Causes

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) is a cattle disease caused by a virus called bovine herpesvirus. Its scientific names are bovine alphaherpesvirus 1 (BoAHV-1) or bovine herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1). This virus belongs to the herpesvirus family and is related to the ones that cause chickenpox in humans and pseudorabies in pigs.

Types of BoHV (Bovine Herpesvirus)

- BoHV-1.1

BoHV-1.1 most commonly links to infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) because it spreads more rapidly. It also produces higher amounts of virus in the respiratory tract. This leads to stronger breathing problems and increases the chances of herd-level outbreaks. It can also cause abortions, adding to its economic impact. - BoHV-1.2

BoHV-1.2 usually causes milder disease, with less severe effects on the respiratory and reproductive systems. Within this type, BoHV-1.2a can lead to abortions, while BoHV-1.2b may infect unborn calves without always causing death. Because of these hidden risks, BoHV-1.2 remains important to monitor, as it can quietly impact herd reproduction.

Structure of the Virus

BoHV-1 is very small, about 150 nanometers in size. It is covered by an outer coat called an envelope, which protects the virus. Inside, it has a strong shell called a capsid that carries its DNA. The DNA gives instructions to make many proteins, some of which are similar to human herpesviruses.

On the outside, the virus has special proteins that help it survive. Some of these proteins are necessary for the virus to grow and multiply. Others do not need for growth but make it easier for the virus to attach to cattle cells and avoid the animal’s defenses destroying it. One special protein, called gE, is essential for vaccines. Removing this protein creates a “marker vaccine.” This vaccine protects cattle but does not produce the same antibodies as natural infection, allowing vets to tell vaccinated animals apart from sick ones.

How the IBR Virus Attacks Animals

BoHV-1 can infect different parts of the body depending on how it enters. It may attack the nose and throat or the reproductive organs. Researchers have also found similar viruses in buffalo, reindeer, goats, elk, and red deer. Once cattle are infected, the virus can hide inside nerve cells and stay there for life. It can become active again during stress and spread through nasal or eye discharge. This means infected cattle can release the virus at any time.

The disease most commonly spreads when an infected animal enters a herd. Economically, IBR is a serious problem. Countries free of the disease do not export cattle with IBR antibodies or use them in artificial insemination centers.

Diagnosis of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis in cattle

While clinical signs may point to infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR), confirmation depends on laboratory testing, particularly in the early stages or when the disease is first suspected in a herd. Lab testing is also essential for telling IBR apart from other respiratory or reproductive diseases with similar symptoms and for ensuring accurate reporting and monitoring.

Sample Collection

Reliable diagnostic samples include nasal swabs, conjunctival swabs, tracheal washes, respiratory secretions, or tissue from aborted fetuses. In some cases, veterinarians may also collect fresh ocular swabs. It is important to place samples in an appropriate transport medium and keep them cool until they reach the laboratory to preserve the virus.

Diagnostic Tests

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction):

PCR is a quick and highly sensitive method that is used to detect the DNA of Bovine Herpesvirus-1 (BoHV-1) in animal samples. It is widely used during outbreaks or in early infection stages because it can confirm the virus quickly and accurately.

Virus Isolation:

This method involves growing the live BoHV-1 virus in a laboratory setting to confirm infection. Although highly accurate, specialists generally perform it in specialised or reference laboratories, particularly when PCR results are unavailable or inconclusive, and it requires more time.

Fluorescent Antibody Test (FAT):

FAT detects BoHV-1 proteins directly in tissue samples. It is often used in abortion investigations or sudden death cases. Standard samples include frozen or refrigerated fetal tissue, placenta, or respiratory tract sections.

ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay):

Veterinarians use ELISA to detect antibodies against BoHV-1 in blood or milk, which indicates current or past infection. It is used primarily for herd surveillance, vaccination monitoring, and control programs. Special formats such as gB ELISA detect antibodies from both infection and vaccination, while gE ELISA detects antibodies from natural infection only.

Virus Neutralisation Test (VNT):

VNT measures the ability of antibodies in an animal’s blood to block viral infection in cell cultures. It is a particular method often used to confirm ELISA results.

Bulk Milk Testing:

This is a herd-level screening method used mainly in dairy herds to detect antibodies in a combined milk sample from the bulk tank. While useful for surveillance, it may miss low-level infections and cannot confirm an IBR-free status.

Only PCR and virus isolation can confirm an active IBR infection, while tests such as ELISA, VNT, FAT, and bulk milk testing help in understanding past exposure, monitoring immunity, and supporting control programs.

Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis Treatment in Cattle

There is no specific treatment for anti-BHV-1, but vaccines for controlling the infection and precautions can help protect your animals. The use of antibiotics to prevent secondary bacterial infections in cattle may also improve survival. Isolate cattle showing symptoms of IBR from the rest of the herd. Use appropriate antibiotics to manage symptoms such as fever, high temperature, loss of appetite, nasal discharge, and refusal to eat.

Treat secondary bacterial infections, which commonly involve Mannheimia haemolytica, with antibiotics based on veterinary guidance. Veterinarians often prescribe non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) to bring down fever and ease inflammation, helping the animal feel more comfortable and recover faster. Supportive care—such as good nutrition, plenty of clean water, and a low-stress environment—also plays an important part in healing. In outbreak situations, the use of an IBR vaccine in cattle that are not yet showing signs of illness may help reduce both the severity of disease and its spread within the herd.

Prevention of Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR) in Cattle

Vaccination is the most effective way to prevent infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) in cattle. Experts consider MLVs (Modified Live Vaccines) more effective than inactivated vaccines because they stimulate stronger and longer-lasting immunity. They reduce the severity of the disease and the chances of it recurring.

In addition, they limit viral shedding, which lowers the risk of the infection spreading between herds. Because of these benefits, they are a practical option for managing IBR in commercial cattle. In the long run, a well-planned vaccination program supports healthier animals and boosts overall herd productivity.

While In small herds, removing cattle that test positive for antibodies works well for achieving complete eradication. In larger herds, however, a gradual culling plan together with systematic vaccination is more practical. Over time, this reduces the spread of the virus and lowers its circulation in the herd.

Importantly, the introduction of replacement animals represents the highest risk for reintroducing IBR in cattle, highlighting the need for quarantine protocols and pre-entry diagnostic testing before herd integration.

Maintaining high biosecurity is equally important for reducing the chance of new infections. Research highlights that closed herds and sourcing cattle only from IBR-free herds will result in reducing disease pressure. Isolate and test newly purchased or returning cattle before mixing them with the main herd. Avoid contact with neighboring cattle through double fencing or by maintaining at least four meters of separation.

People, equipment, and vehicles can also act as mechanical carriers of the virus. Farm workers recommend using farm-specific clothing, disinfecting boots, and controlling visitor access. Use reproductive material such as semen and embryos only if certification confirms they are free from BoHV-1.These preventive practices provide high effectiveness, but cattle achieve maximum protection only when they combine them with the structured use of an IBR vaccine.

Types of IBR Cattle Vaccines

There are four types of vaccines for IBR: Live (Injectable) Vaccine, Live (Intranasal) Vaccine, Inactivated Vaccine, and Marker (DIVA) Vaccine. Here is how each of these IBR vaccines is used.

| Vaccine Type | Features | Best Use |

| Live (Injectable) | Induces strong systemic immunity; not safe in pregnant cows | Outbreak control, rapid herd protection |

| Live (Intranasal) | Stimulates local nasal immunity; short duration | Quick protection in calves or stressed animals |

| Inactivated (Killed) | Safe for all ages and pregnant cows; requires boosters | Long-term herd programs, eradication schemes |

| Marker (DIVA) | Distinguishes infected from vaccinated cattle | Eradication and trade certification |

Scientific evidence supports that live vaccines (injectable or intranasal) provide rapid and strong immune responses. Injectable live vaccines may cause abortion, so veterinarians do not recommend them for pregnant cows, whereas they safely use intranasal forms in calves and stressed cattle for quick protection.

Veterinarians widely recognize inactivated (killed) vaccines as the safest option because they can be used in all age groups, including pregnant cows. Farmers must give booster doses to maintain immunity. Marker (DIVA) vaccines are particularly important in eradication programs, as they allow veterinarians to identify whether antibodies are due to natural infection or vaccination, which supports accurate monitoring and disease-free certification.

Commonly Used IBR Cattle Vaccines

The most commonly used vaccines for IBR are Rispoval IBR Live and Hiprabovis IBR Marker Live, which are live vaccines, whereas Rispoval IBR Marker Inac, Tracherine, and Hiprabovis IBR Marker Inac are inactivated vaccines. Here is how they are used:

| Vaccine Name | Type | Safe in Pregnant Cows? | Usage |

| Rispoval IBR Live | Live (Intranasal/Inject.) | ❌ No (injectable form unsafe in pregnancy) | Outbreak control, rapid immunity |

| Rispoval IBR Marker Inac | Inactivated (Marker) | ✅ Yes | Safe long-term herd use, eradication support |

| Tracherine | Inactivated | ✅ Yes | Long-term herd protection |

| Hiprabovis IBR Marker Live | Live (Marker) | ❌ No (not for pregnant cows) | Quick protection with DIVA benefits |

| Hiprabovis IBR Marker Inac | Inactivated (Marker) | ✅ Yes | Trade and eradication programs. |

Field data show that combining vaccination with routine monitoring provides the most sustainable protection strategy. Calves vaccinated before three months of age may require additional booster doses due to interference from maternal antibodies. Veterinarians usually advise re-vaccinating herds every six months to keep immunity levels strong. Farmers can monitor BoHV-1 by using bulk milk antibody tests and occasional blood samples, which helps them adjust herd health plans when needed.

Some other diseases caused by BHV-1

BHV-1 can infect the reproductive system, often through breeding. In cows, it causes Infectious Pustular Vulvovaginitis (IPV), Infectious Pustular Balanoposthitis (IPB), and Abortion / early embryo death.

Infectious Pustular Vulvovaginitis (IPV) which leads to vulva and vaginal swelling, followed by small pus-filled spots that merge into a yellow-white layer. Most lesions heal within 10–14 days, but some animals develop persistent pus-like discharge and uterine inflammation, and bacteria can cause temporary infertility.

In bulls, it causes Infectious Pustular Balanoposthitis (IPB), which leads to prepuce swelling, thick pus-like discharge, and painful mating, sometimes reducing breeding interest. These lesions also heal in 10–14 days unless complicated by bacteria. Abortion may occur during or up to 100 days after a respiratory outbreak, usually in late pregnancy, though early embryo death is also possible. Such effects can happen even if the dam showed mild illness during the initial infection.

Conclusion

Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) continues to pose a significant threat to cattle health because of its ability to remain latent and reactivate under stress. Since no curative treatment is available, prevention and control remain the most practical solutions. Strict biosecurity and quarantine of new animals help block the entry of the virus into herds.

Vaccination, along with routine monitoring, is key to lowering infection pressure and protecting herd immunity. In smaller herds, selectively removing antibody-positive cattle can be very effective, whereas larger herds often benefit more from combining vaccination with gradual culling. Marker vaccines are especially useful, as they not only help control the disease but also make it possible to tell apart vaccinated animals from those naturally infected, which is important for trade. When applied together, these measures create a solid and practical foundation for the long-term prevention of IBR in cattle.

FAQs related to Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) in cattle

What is the cause of IBR in cattle?

IBR in cattle is caused by Bovine Herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1), a highly contagious virus.

The infection spreads through nasal discharge, coughing, semen, and contaminated equipment.

Newly introduced infected animals act as the primary source of transmission within a herd.

What is the treatment for IBR?

What is the IBR test for cattle?

The IBR test for cattle is a diagnostic test used to detect antibodies or the presence of Bovine Herpesvirus type 1 (BoHV-1). Common tests include ELISA, virus isolation, and PCR, which help determine if an animal is currently infected or has been exposed in the past. These tests are used for herd surveillance, vaccination monitoring, and disease control programs.

Can cattle recover from IBR?

Yes, cattle can recover from IBR, but recovery depends on the severity of the infection and the animal’s overall health. Most cattle recover with supportive care, including proper nutrition, stress reduction, and treatment of secondary bacterial infections. Vaccination and good herd management help prevent severe cases and reduce the risk of reinfection.

How do you identify IBR?

IBR in cattle can be identified by observing clinical signs such as fever, nasal discharge, coughing, red eyes (conjunctivitis), loss of appetite, and reduced milk production, with abortions occurring in severe cases. For accurate confirmation, veterinarians use diagnostic tests like ELISA to detect antibodies, PCR to identify viral DNA, and virus isolation to confirm the virus. Combining symptom observation with laboratory testing ensures precise identification and helps guide appropriate management and treatment measures.

When to vaccinate cows for IBR?

Cows should be vaccinated for IBR based on age, herd status, and risk of exposure. Calves are usually vaccinated at 2–6 months of age, with a booster 3–6 weeks later. Adult cows, especially pregnant or newly introduced animals, should receive vaccination as part of herd health programs. Regular annual or biannual boosters are recommended to maintain immunity and prevent outbreaks.